Tutorial

Experienced Julia users and programmers fluent in other languages and graphics systems should have no problem using Luxor by referring to the rest of the documentation. For others, here is a short tutorial to help you get started.

What you need

If you've already downloaded Julia, and have added the Luxor package successfully (like this):

Pkg.add("Luxor")then you're ready to start.

Presumably you'll be working in a Jupyter notebook, or perhaps using the Atom/Juno editor/development environment. It's also possible to work in a text editor (make sure you know how to run a file of Julia code), or, at a pinch, you could use the Julia REPL directly.

Ready? Let's begin. The goal of this tutorial is to do a bit of basic 'compass and ruler' Euclidean geometry, to introduce the basic concepts of Luxor drawings.

First steps

Have you started a Julia session? Excellent. We'll have to load just one package for this tutorial:

using LuxorHere's an easy shortcut for making drawings in Luxor. It's a Julia macro, and it's a good way to test that your system's working. Evaluate this code:

@png begin

text("Hello world")

circle(Point(0, 0), 200, :stroke)

endWhat happened? Can you see this image somewhere?

If you're using Juno, the image should appear in the Plots window. If you're working in a Jupyter notebook, the image should appear below the code. If you're using Julia in a terminal or text editor, the image should have opened up in some other application, or, at the very least, it should have been saved in your current working directory (as luxor-drawing.png). If nothing happened, or if something bad happened, we've got some set-up or installation issues probably unrelated to Luxor...

Let's press on. The @png macro is an easy way to make a drawing; all it does is save a bit of typing. (The macro expands to enclose your drawing commands with calls to the Document(), origin(), finish(), and preview() functions.) There are also @svg and @pdf macros, which do a similar thing. PNGs and SVGs are good because they show up in Juno and Jupyter. SVGs are often higher quality too, but they're text-based so can become very large for complex images. PDF documents are always higher quality, and usually open up in a separate application.

This example illustrates a few things about Luxor drawings:

There are default values which you don't have to set if you don't want to (file names, colors, font sizes, etc).

Positions on the drawing are specified with coordinates stored in the Point datatype, and you can sometimes omit positions altogether.

The text was placed at the origin point (0,0), and by default it's left aligned.

The circle wasn't filled, but

stroked. We passed the:strokesymbol as an action to thecircle()function. Many drawing functions expect some action, such as:fillor:stroke, and sometimes:clipor:fillstroke.Did the first drawing takes a few seconds to appear? The Cairo drawing engine takes a little time warm up. Once it's running, drawings appear much faster.

Once more, with more black, and some rulers:

@png begin

text("Hello again, world!", Point(0, 250))

circle(Point(0, 0), 200, :fill)

rulers()

end

Euclidean eggs

For the main section of this tutorial, we'll attempt to draw Euclid's egg, which involves a bit of geometry.

For now, you can continue to store all the drawing instructions between the @png macro's begin and end markers. Technically, however, working like this at the top-level in Julia (ie without storing instructions in functions which Julia can compile) isn't considered to be 'best practice'.

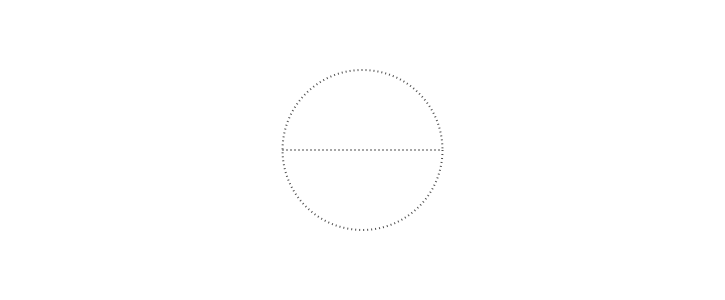

@png beginTo start off, define the variable radius to hold a value of 80 units (there are 72 units in a traditional inch):

radius=80Select gray dotted lines. To specify a color you can supply RGB (or HSB or LAB or LUV) values or use named colors, such as "red", "gray0" is black, and "gray100" is white. (For more details about colors, see Colors.jl.)

setdash("dot")

sethue("gray30")Next, make two points, A and B, which will lie either side of the origin point. This line uses an array comprehension - notice the square brackets enclosing a for loop. x uses two values from the inner array, and a Point using each value is created and stored in a new array. It seems hardly worth doing for two points. But it shows how you can assign more than one variable at the same time, and also how to generate more than two points...

A, B = [Point(x, 0) for x in [-radius, radius]]With two points defined, draw a line from A to B, and "stroke" it.

line(A, B, :stroke)Draw a stroked circle too. The center of the circle is placed at the origin. You can use the letter 'O' as a short cut for Origin, ie the Point(0, 0).

circle(O, radius, :stroke)

end

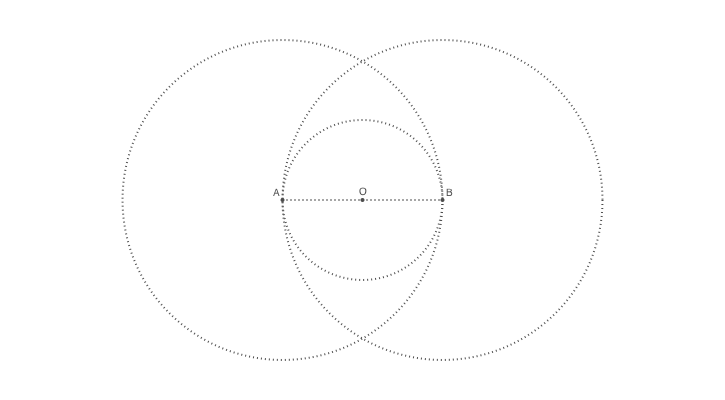

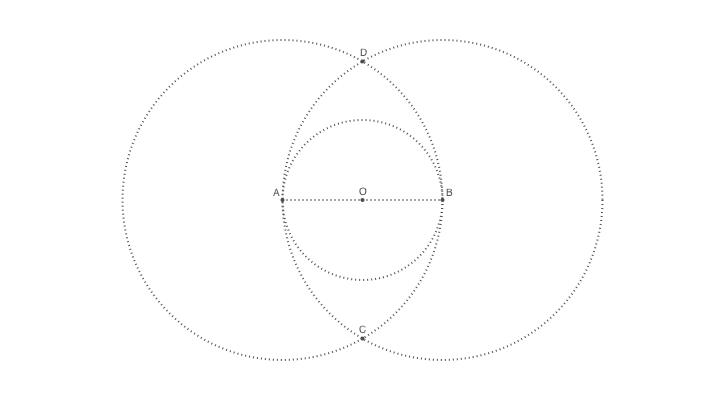

Labels and dots

It's a good idea to label points in geometrical constructions, and to draw small dots to indicate their location clearly. For the latter task, small filled circles will do. For labels, there's a special label() function we can use, which positions a text string close to a point, using points of the compass, so :N places the label to the north of a position.

Edit your previous code by adding instructions to draw some labels and circles:

@png begin

radius=80

setdash("dot")

sethue("gray30")

A, B = [Point(x, 0) for x in [-radius, radius]]

line(A, B, :stroke)

circle(O, radius, :stroke)

label("A", :NW, A)

label("O", :N, O)

label("B", :NE, B)

circle.([A, O, B], 2, :fill)

circle.([A, B], 2radius, :stroke)

end

While we could have drawn all the circles as usual, we've taken the opportunity to introduce a powerful Julia feature called 'broadcasting'. The dot ('.') just after the function name in the last two circle() function calls tells Julia to apply the function to all the arguments. We supplied an array of three points, and filled circles were placed at each one. Then we supplied an array of two points and stroked circles were placed there. Notice that we didn't have to supply an array of radius values or an array of actions — in each case Julia did the necessary broadcasting (from scalar to vector) for us.

Intersect this

We've now ready to tackle the job of finding the coordinates of the two points where two circles intersect. There's a Luxor function called intersectionlinecircle() that finds the point or points where a line intersects a circle. So we can find the two points where one of the circles crosses an imaginary vertical line drawn through O. Because of the symmetry, we'll only have to do circle A.

@png begin

# as before

radius=80

setdash("dot")

sethue("gray30")

A, B = [Point(x, 0) for x in [-radius, radius]]

line(A, B, :stroke)

circle(O, radius, :stroke)

label("A", :NW, A)

label("O", :N, O)

label("B", :NE, B)

circle.([A, O, B], 2, :fill)

circle.([A, B], 2radius, :stroke)The intersectionlinecircle() takes four arguments: two points to define the line and a point/radius pair to define the circle. It returns the number of intersections (probably 0, 1, or 2), followed by the two points.

The line is specified with two points with an x value of 0 and y values of ± twice the radius, written in Julia's math-friendly style. The circle is centered at A and has a radius of AB (which is 2radius). Assuming that there are two intersections, we feed these to circle() and label() for drawing and labeling using our new broadcasting superpowers.

nints, C, D =

intersectionlinecircle(Point(0, -2radius), Point(0, 2radius), A, 2radius)

if nints == 2

circle.([C, D], 2, :fill)

label.(["D", "C"], :N, [D, C])

end

end

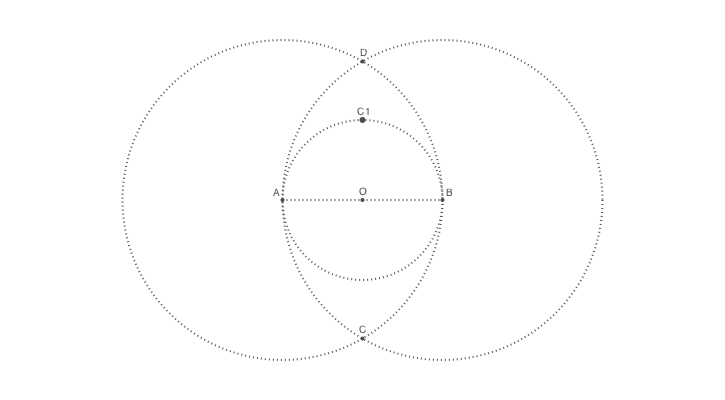

The upper circle

Now for the trickiest part of this construction: a small circle whose center point sits on top of the inner circle and that meets the two larger circles near the point D.

Finding this new center point C1 is easy enough, because we can again use intersectionlinecircle() to find the point where the central circle crosses a line from O to D.

Add some more lines to your code:

@png begin

# ...

nints, C1, C2 = intersectionlinecircle(O, D, O, radius)

if nints == 2

circle(C1, 3, :fill)

label("C1", :N, C1)

end

end

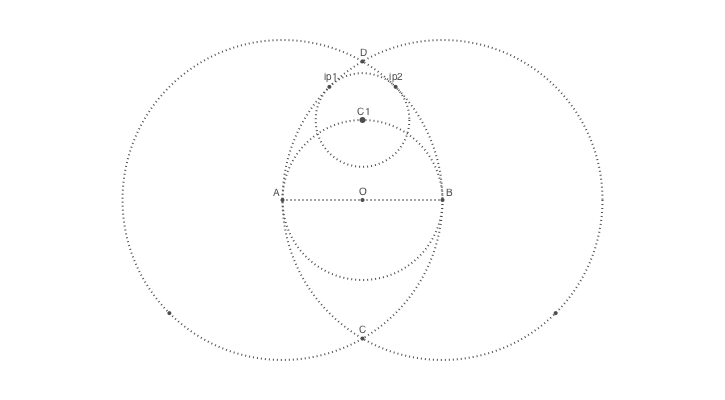

The two other points that define this circle lie on the intersections of the large circles with imaginary lines through points A and B passing through the center point C1.

To find (and draw) these points is straightforward, but we'll mark these as intermediate for now, because there are four intersection points but we want just the two nearest the top:

@png begin

# ...

nints, I3, I4 = intersectionlinecircle(A, C1, A, 2radius)

nints, I1, I2 = intersectionlinecircle(B, C1, B, 2radius)

circle.([I1, I2, I3, I4], 2, :fill)The distance() function returns the distance between two points, and it's simple enough to compare the distances.

if distance(C1, I1) < distance(C1, I2)

ip1 = I1

else

ip1 = I2

end

if distance(C1, I3) < distance(C1, I4)

ip2 = I3

else

ip2 = I4

end

label("ip1", :N, ip1)

label("ip2", :N, ip2)

circle(C1, distance(C1, ip1), :stroke)

end

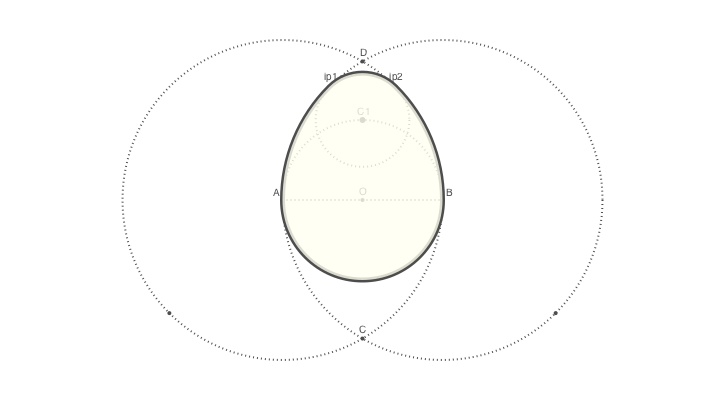

Eggs at the ready

We now know all the points on the egg's perimeter, and the centers of the circular arcs. To draw the outline, we'll use the arc2r() function four times. This function takes: a center point and two points that together define a circular arc, plus an action.

The shape consists of four curves, so we'll use the :path action. Instead of immediately drawing the shape, like the :fill and :stroke actions do, this action adds a section to the current path (which is initially empty).

@png begin

# ... as before

# Add this:

setline(5)

setdash("solid")

arc2r(B, A, ip1, :path) # centered at B, from A to ip1

arc2r(C1, ip1, ip2, :path)

arc2r(A, ip2, B, :path)

arc2r(O, B, A, :path)Once we've added all four sections to the path we can stroke and fill it. If you want to use separate styles for the stroke and fill, you can use a "preserve" version of the first action. This applies the action but keeps the path around for more actions.

strokepreserve()

setopacity(0.8)

sethue("ivory")

fillpath()

end

Egg stroke

To be more generally useful, the above code can be boiled into a single function.

function egg(radius, action=:none)

A, B = [Point(x, 0) for x in [-radius, radius]]

nints, C, D =

intersectionlinecircle(Point(0, -2radius), Point(0, 2radius), A, 2radius)

flag, C1 = intersectionlinecircle(C, D, O, radius)

nints, I3, I4 = intersectionlinecircle(A, C1, A, 2radius)

nints, I1, I2 = intersectionlinecircle(B, C1, B, 2radius)

if distance(C1, I1) < distance(C1, I2)

ip1 = I1

else

ip1 = I2

end

if distance(C1, I3) < distance(C1, I4)

ip2 = I3

else

ip2 = I4

end

newpath()

arc2r(B, A, ip1, :path)

arc2r(C1, ip1, ip2, :path)

arc2r(A, ip2, B, :path)

arc2r(O, B, A, :path)

closepath()

do_action(action)

endThis keeps all the intermediate code and calculations safely hidden away, and it's now possible to draw a Euclidean egg by calling egg(100, :stroke), for example, where 100 is the required width (radius), and :stroke is the required actions.

(Of course, there's no error checking. This should be added if the function is to be used for any serious applications...!)

Notice that this function doesn't define anything about what the shape looks like or where it's placed. When called, the function inherits the current drawing environment: scale, rotation, position, line thickness, color, style, and so on. This lets us write code like this:

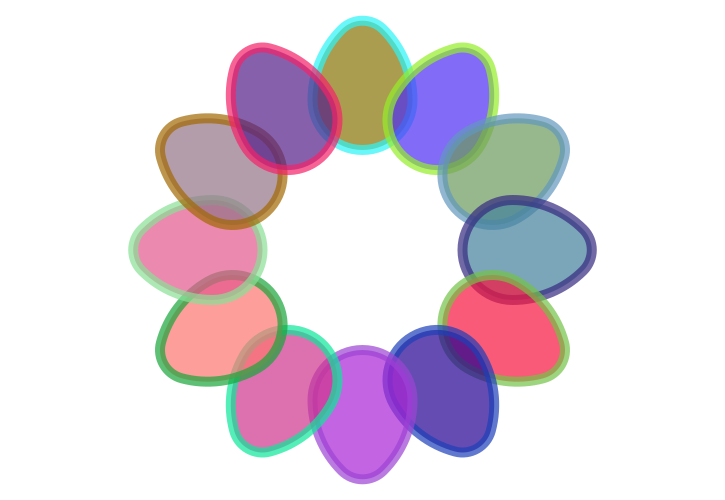

@png begin

setopacity(0.7)

for theta in range(0, step=pi/6, length=12)

@layer begin

rotate(theta)

translate(0, -150)

egg(50, :path)

setline(10)

randomhue()

fillpreserve()

randomhue()

strokepath()

end

end

end

The loop runs 12 times, with theta increasing from 0 upwards in steps of π/6. But before each egg is drawn, the entire drawing environment is rotated by theta radians and then shifted along the y-axis away from the origin by -150 units (the y-axis values usually increase downwards, so, before any rotation takes place, a shift of -150 looks like an upwards shift). The randomhue() function does what you expect, and the egg() function is passed the :fill action and the radius.

Notice that the four drawing instructions are encased in a @layer begin...end "shell". Any change made to the drawing environment inside this shell is discarded after each end. This allows us to make temporary changes to the scale and rotation, etc. and discard them easily once the shapes have been drawn.

Rotations and angles are typically specified in radians. The positive x-axis (a line from the origin increasing in x) starts off heading due east from the origin, and the y-axis due south, and positive angles are clockwise (ie from the positive x-axis towards the positive y-axis). So the second egg in the previous example was drawn after the axes were rotated by π/6 radians clockwise.

If you look closely you can tell which egg was drawn first — it's overlapped on each side by subsequent eggs.

Thought experiments

What would happen if the translation was

translate(0, 150)rather thantranslate(0, -150)?What would happen if the translation was

translate(150, 0)rather thantranslate(0, -150)?What would happen if you translated each egg before you rotated the drawing environment?

Some useful tools for investigating the important aspects of coordinates and transformations include:

rulers()to draw the current x and y axesgetrotation()to get the current rotationgetscale()to get the current scale

Polyeggs

As well as stroke and fill actions, you can use the path as a clipping region (:clip), or as the basis for more shape shifting.

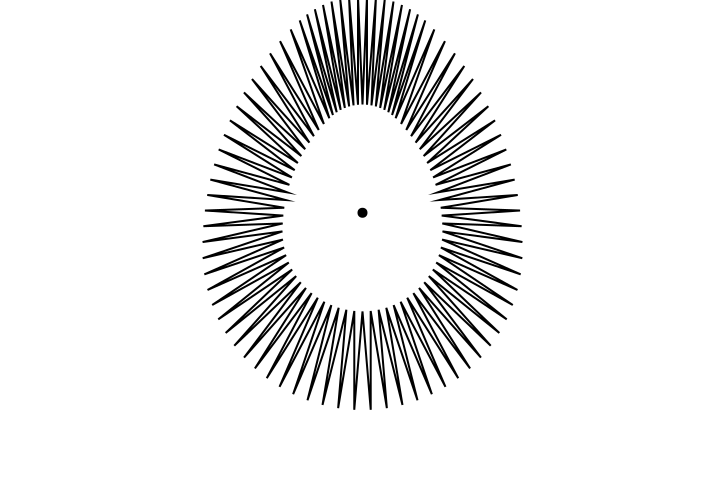

The egg() function creates a path and lets you apply an action to it. It's also possible to convert the path into a polygon (an array of points), which lets you do more things with it. The following code converts the egg's path into a polygon, and then moves every other point of the polygon halfway towards the centroid.

@png begin

egg(160, :path)

pgon = first(pathtopoly())The pathtopoly() function converts the current path made by egg(160, :path) into a polygon. Those smooth curves have been approximated by a series of straight line segments. The first() function is used because pathtopoly() returns an array of one or more polygons (paths can consist of a series of loops), and we know that we need only the single path here.

pc = polycentroid(pgon)

circle(pc, 5, :fill)polycentroid() finds the centroid of the new polygon.

This loop steps through the points and moves every odd-numbered one halfway towards the centroid. between() finds a point midway between two specified points. The poly() function draws the array of points.

for pt in 1:2:length(pgon)

pgon[pt] = between(pc, pgon[pt], 0.5)

end

poly(pgon, :stroke)

end

The uneven appearance of the interior points here looks to be a result of the default line join settings. Experiment with setlinejoin("round") to see if this makes the geometry look tidier.

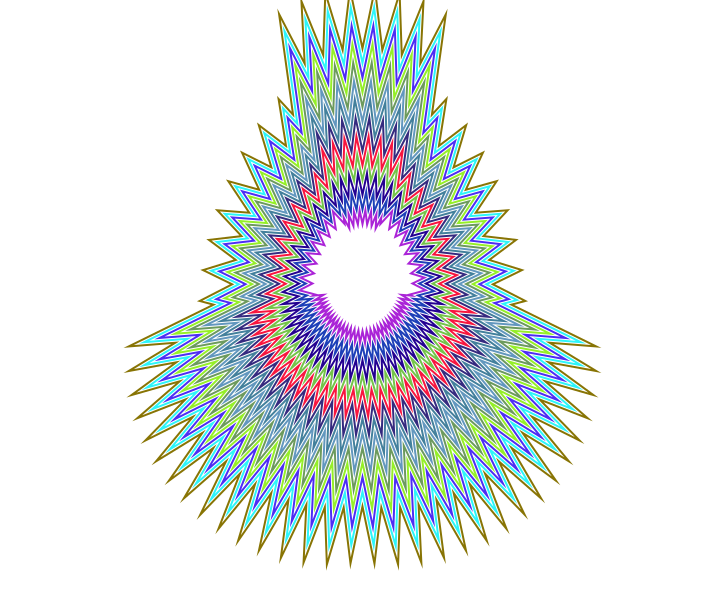

For a final experiment with our egg() function, here's Luxor's offsetpoly() function struggling to draw around the spiky egg-based polygon.

@png begin

egg(80, :path)

pgon = first(pathtopoly())

pc = polycentroid(pgon)

circle(pc, 5, :fill)

for pt in 1:2:length(pgon)

pgon[pt] = between(pc, pgon[pt], 0.8)

end

for i in 30:-3:-8

randomhue()

op = offsetpoly(pgon, i)

poly(op, :stroke, close=true)

end

end

The slight changes in the regularity of the points (originally created by the path-to-polygon conversion and the varying number of samples it made) are continually amplified in successive outlinings.

Clipping

A useful feature of Luxor is that you can use shapes as a clipping mask. Graphics can be hidden when they stray outside the boundaries of the mask.

In this example, the egg (assuming you're still in the same Julia session in which you've defined the egg() function) isn't drawn, but is defined to act as a clipping mask. Every graphic shape that you draw now is clipped where it crosses the mask. This is specified by the :clip action which is passed to the doaction() function at the end of the egg().

Here, the graphics are provided by the ngon() function, which draws regular n-sided polygons.

using Luxor, Colors

@svg begin

setopacity(0.5)

eg(a) = egg(150, a)

sethue("gold")

eg(:fill)

eg(:clip)

@layer begin

for i in 360:-4:1

sethue(Colors.HSV(i, 1.0, 0.8))

rotate(pi/30)

ngon(O, i, 5, 0, :stroke)

end

end

clipreset()

sethue("red")

eg(:stroke)

end

It's usually good practice to add a matching clipreset() after the clipping has been completed.

Good luck with your explorations!